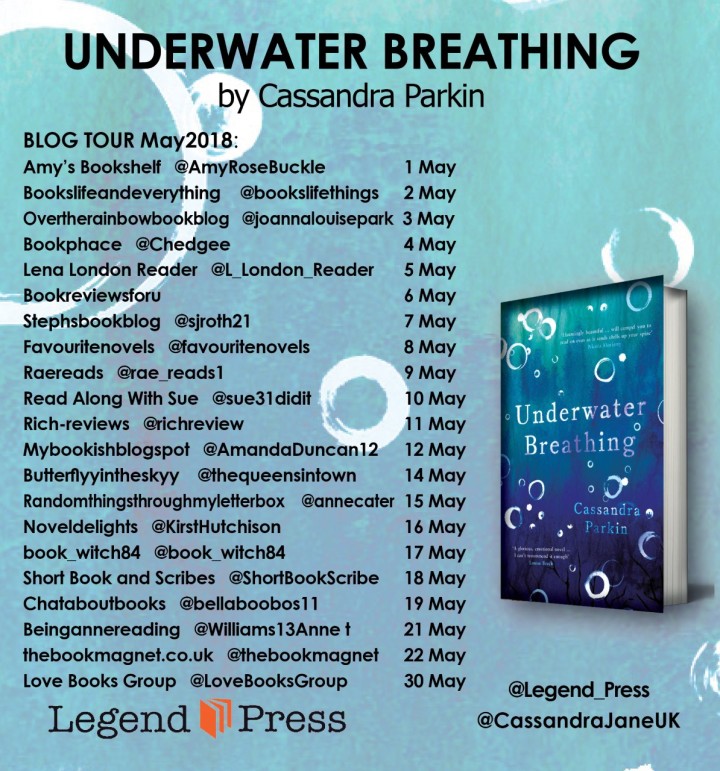

I’m thrilled to be joining in with Cassandra Parkin’s Underwater Breathing blog tour today! 🙂 I have an extract and giveaway as part of my stop, with thanks to Imogen at Legend Press.

UNDERWATER BREATHING

CASSANDRA PARKIN

ISBN (Paperback): 9781787198401

ISBN (Ebook): 9781787198395

Price: £8.99 (Paperback) £4.99 (Ebook)

Extent: 320 pages

Format: 198x129mm

Rights Held: World

On Yorkshire’s gradually-crumbling mud cliffs sits an Edwardian seaside house. In the bathroom, Jacob and Ella hide from their parents’ passionate arguments by playing the ‘Underwater Breathing’ game – until the day Jacob wakes to find his mother and sister gone. Years later, the sea’s creeping closer, his father is losing touch with reality and Jacob is trapped in his past. Then, Ella’s sudden reappearance forces him to confront his fractured childhood. As the truth about their parents emerges, it’s clear that Jacob’s time hiding beneath the water is coming to an end.

Can a crumbling family structure mend the ties that bind them?

Extract…..

Chapter Two

2007

On the third morning in their house at the end of the world, Jacob woke to sunshine and silence and a sky that stretched out and out like a flat blue sheet. He lay in bed for a few minutes, listening to the small sounds of the house as it moved and settled. He was still learning the personality of this new home. The warm places and the draughty ones. The spots where you could walk freely and the ones where the boards would shriek like mandrakes. The welcoming rooms and the ones that brimmed with darkness. After so many years of smallness and making do, the emptiness and light made him feel as if the top of his head might come off. So far, this house seemed worn but welcoming, the way he imagined it would feel to visit grandparents. He wondered if the house knew it was destined to fall into the sea eventually, or if it believed it would stand for ever, as solid and permanent as the day it was first built. In the corridor outside, a small sound like a mouse told him Ella was there. After a minute, the door moved slightly and half of her face peered cautiously in. “It’s too early,” he told her, not because it was too early but because he wanted her to start learning that it wasn’t okay to come into his room without being asked. Then, because her face looked so resigned and sad as she turned away, he added, “but you can come in anyway. As long as you don’t fidget.” A scurry of feet and a glad little hop and his bed was full of Ella, smelling of clean childish sweat and strawberry shampoo. At six, she was getting too big to do this; her sharp little toes scratched against his leg as she wriggled beneath the covers. He’d been exactly the right temperature when he woke up, but with Ella beside him the bed was like a superheated prison. He’d have to get up soon. “Do you like our new house?” he asked. To his surprise, she immediately shook her head. “You don’t? Seriously? Why not?” She whispered something, but he couldn’t make it out. “Don’t whisper, I can’t understand you. Talk to me properly.” She looked at him silently. “Fine, don’t talk to me properly, that’s up to you. Come on. It’s breakfast time.” His room and Ella’s were at one end of a short corridor that terminated in a rounded turret. When they first looked at the house, he’d seen the turret from the outside and hoped it might be his bedroom. As it turned out, the turret room was a cavernous bathroom that his parents had instantly told them both they were never to use – a rule Jacob took great secret pleasure in ignoring. He shut the bathroom door on Ella’s hopeful face. He wasn’t going to have her watching him pee. When he opened the door again, her expression reminded him of a dog waiting for its owner. “I waited for you,” she said, and took his hand confidingly. “You did.” “Are we going downstairs now?” “We are.” “Shall we have breakfast now?” “Yes.” “And Mummy and Daddy aren’t awake yet?” “I don’t know.” It was still strange to find himself in a space where every action of every person in the household wasn’t instantly telegraphed, not just to everyone in their own home, but to everyone in the homes on either side and on top of them as well. “We’ll go past their bedroom and listen.” “Did they argue last night?” The sudden question pierced him. He’d wanted to believe that, with this new home, the shouting would stop. “No, I don’t think so.” Lying to his little sister felt wrong, even when it was for her own good. “You didn’t hear anything, did you?” “Yes.” “You can’t have done, you were asleep. You must have dreamed it.” “I woke up and I couldn’t sleep again because I was frightened. I don’t like it here. The sea’s too close. It’s going to come and take our house away.” “Don’t be silly, the sea’s not going to take our house away.” “Yes it is, that’s what the man said. It’s going to come in the night when it’s raining and take our house away and we’ll all go floating in the water and never see each other again.” “Stop it. That won’t happen. Well, it might happen in the end, but not for years. Now come on, we’re going to find some breakfast.” The door to their parents’ bedroom was closed as they passed it. He paused a moment in case he could hear anything, get a measure of the emotional temperature of the household, but there was nothing. The acoustics here were another mystery he was still exploring. Sometimes you could stand by a halfopened door and hear almost nothing of what was being said on the other side. Sometimes you could be three rooms away and a voice would come to him with startling clarity. (“My head’s like a beehive,” his mother had said yesterday as he stood in the tiled room by the front door, idly contemplating the patches of damp that bloomed across the bare walls, and he was so convinced that she was behind him and speaking to him that he turned to ask her what she meant. “And you’re like a beekeeper. You keep the bees in order and stop them from swarming too far.” And it was only when his father replied, “So do the bees like it here?” that he realised he was standing beneath their bedroom and eavesdropping on their private conversation.) They left their parents’ room and went downstairs. The flowing wooden curve of the bannister beneath his hand felt like an old friend. He had to stop himself from laughing out loud as the hallway came up to meet him. The kitchen smelled of last night’s dinner – a chicken curry that had been delicious at the time, but now just smelled gross. He wrestled with the back door for a while, until finally a gust of warm clean air rushed in. Another glorious thing about their new home: the garden that came with it. He still couldn’t quite believe it was all theirs. “Do you want a picnic?” he asked Ella. She was rummaging in the cupboard where she’d insisted on stashing her own special plastic cups and plates. Her face looked at him doubtfully over the top of the door. “Come on, let’s go outside and eat. It’s warmer outside than in here.” The breeze tugged at his hair and the legs of his pyjamas. “My feet will get cold.” “Put your wellies on.” “It’ll be all wet.” “No it won’t.” “I don’t like it outside, I’d rather eat inside –” “I’ll get your wellies for you. Don’t try and make breakfast, I’ll do it.” He crammed the toaster with bread, then sprinted to the tiled room by the front door, which his mother had now declared to be the cloakroom. If he wasn’t quick enough, Ella would think he wasn’t coming back at all and would start assembling her own breakfast, which was unlikely to end well. Ella’s wellies – purple and white with a unicorn face moulded into the toes, a magical charity-shop discovery – lay at rest between his father’s muddy work boots. As he picked them up, he heard his parents speaking in the room above, and paused a moment, holding his breath so he could hear more clearly. “We shouldn’t have come here.” His mother, her voice low and full of conviction. “It’s too quiet.” We belong here, Jacob thought furiously, trying to send his thoughts up through the ceiling and into his parents’ brains. Don’t argue. Please don’t argue. This is our home, we’ve finally got one. Don’t ruin it. “And that’s exactly why we bought it! Because it’s quiet. We’ll be safe here. End of the world and turn right, remember?” “But if the world ends and we turn right, do you know where we’ll be?” A little frightened laugh. “The sea wants the house too.” “We’ve got time. We’ve got at least twenty years, that’s what they said. Isn’t that enough for now?” “And you’re drinking again. Don’t tell me you’re not because I know you are, I could smell it on you last night.” “We were celebrating! Last of the unpacked boxes? You had some too.” “I saw you drink three glasses of wine and a glass of whiskey with me, and I saw you down three fingers of whiskey in the pantry and then refill your glass and bring it out again.” No, thought Jacob, don’t do this, stop it. Don’t ruin this house. “Are you spying on me?” “No. Yes. Yes, I was. I spied with my little eye. I’m good at watching you, I have to be.” “For God’s sake! Look, that’s all in the past, isn’t it? It was a hard life for both of us and we both had our ways of coping, didn’t we? And sometimes – sometimes – I used to drink a bit more than I ought to. But now we’re here and we’re safe, so you can stop looking over your shoulder all the time, and I –” “Can stop drinking in secret?” “It wasn’t a secret, it was an impulse. I had one extra mouthful of the good stuff because I was happy and then I came out. It wasn’t three fingers, it wasn’t even three millimetres, it was just a little mouthful. You’re exaggerating again. And I wasn’t drunk, I’m never drunk.” A brief silence. “Now why don’t you come here?” The sound of feet moving above him, and then a single murmur of pleasure with two notes to it that sent him scurrying to the doorway, Ella’s boots clutched tightly in his fingers. He’d been listening at doors since his father’s first hesitant question (“Jacob, would it be all right if I brought a girlfriend home one time?”) – but his parents doing that wasn’t something he wanted to listen to ever. In the kitchen, he found imminent disaster. Ella, industriously busy as she always was when left to herself, had used a chair to climb the worktops, opened all the cupboards until she found the Cheerios, filled her bowl and the surrounding floor with crunchy cereal hoops, climbed another chair to reach the fridge and taken out the milk. Now she was struggling with the screw-top, her mouth open with concentration and her hair tousled and fluffy in the sunlight. He yelped in panic, took the milk from her and put it out of reach. “I told you not to try and get your own breakfast,” he said, unsure whether to tell her off or admire her persistence. “Never mind. Put your wellies on.” That garden! His heart lifted every time he caught a glimpse of its wild neglected tangle. (“It used to be bigger,” the vendor said ruefully as he showed them around a lawn bursting with dandelions, bounded with rose bushes at the sides and with a scrub of brambles and gorse marking the spot where the garden spilled onto the cliffs.) Jacob didn’t care about how big it had once been; what they had now was astounding. In the middle of the lawn, a crabbed old apple-tree crouched over a patch of barren earth made briefly lovely with fallen blossom. Ella made a beeline for the spot beneath the tree, milk and cereal slopping out of the sides of the bowl as she went.

“Come on,” he coaxed Ella. “Let’s go closer to the sea.” She shook her head. “We might see a seal. Like in your animal book?” “I want to sit under the tree.” “No, we’ll sit where we can see the water at least.” She shut her eyes and turned away. “There’s a beach down there. We could paddle maybe. Look for shells. Come on Ella, don’t be a pain. I’ve done everything you want so far, I spent ages yesterday helping you get your room sorted, now it’s time to do something I want.” “No. I don’t want to see the sea, I want to stay here and play in the garden.” “Well, if you won’t come with me then I’m going on my own,” he declared, and marched off with his toast, knowing he’d just invoked the nuclear option and she would follow him, because she worshipped him. He wasn’t being fair, but then it wasn’t fair that he’d spent most of yesterday unpacking clothes into drawers and books into bookshelves while she endlessly rearranged six plastic unicorns along her window ledge, so now he got to cancel out that unfairness with a bit of his own. He heard Ella scurrying behind him. She had discarded her cereal bowl somewhere in the garden. After a minute he took her hand in his and gave it a squeeze. Sharing Jacob’s toast between them, they pushed through the grudging gap in the tangle of gorse and brambles that marked what Jacob presumed was the end of their garden. The spines of the gorse glinted with the raindrops it had captured last night. (“Now everything will grow,” his mother had said dreamily, looking out of the window. “Like having a gardener come for free. Free rain. And tomorrow you kids can have free rein…”) Beyond the thin thread of pathway, the cliff-edge rushed downwards. “Is this still our garden?” Ella whispered. “Are we still in our garden?” “I don’t know. Maybe.”

“There’s a path, though. Are people allowed to make a path in our garden?” “I don’t think anyone really comes here anyway. It’s too –” he stopped before the word dangerous could get away from him – “too quiet.” “So who made the path then? Jacob, what if people can come in our garden?” At the foot of the cliff, an empty, shingly beach had rolled itself out. Sunlight washed over the pebbles and struck sparks off the water. A rowboat bobbed a few feet from the shore, oars resting on the cross-struts that braced its wide-bellied shape. There was no sign of the boat’s owner. “We could maybe get a boat,” he said. Ella shook her head. “Come on, it could be fun.” “I don’t want to go in a boat, they’re dangerous.” “No, they’re not. Shall we go down there?” “Please can we go back to the house now?” “No, let’s explore.” A crumbly brown pathway led like a slipway onto the pebbles below. It looked steep but doable. “Hey, this might even be our own private beach. How cool would that be?” “I don’t want to go on the beach, please Jacob, I don’t want to go on the beach.” He picked her up and slung her across his hip. “No, please put me down, put me down, please, Jacob, please –” “Shush. You’ll like it when we get there. And stop wriggling or I’ll drop you.” He scrabbled down the slope. Ella was a dead weight in his arms, fingers hooked into him like claws. He would have bruises later. The sand was as deserted as it had looked from above. They might be the only people left alive in the world. Against his chest, Ella was like a vibrating drum. “Come on,” he said coaxingly, half-ashamed now he’d got his way. “It’s lovely down here. Do you want to paddle?” She shook her head. “We can play some games if you like, or just collect stones and stuff. What’s the matter now?”

Ella pointed to the slick black shape that lay, basking in the sunshine, a few feet from the base of the cliff. “Is it a monster?” she whispered. “Is it? Will it get us?” “Oh, wow.” Jacob’s heart swelled with gladness. “Oh, wow, that’s a seal. Ella, that’s a seal.” “It looks like a monster.” Her fingers were slackening their death-grip on his arms. He put her down before she could grab on again. “Is it really a seal? An alive one? Not a toy one?” “Of course an alive one, who’d make a toy seal that big? Do you want to go closer?” “Should we stroke it?” “Definitely not, but we can look.” “Would it be soft?” “I don’t know, it might be, I know they’re furry but I don’t know what they feel like.” There was something odd about the seal’s shape; it was thinner than he’d thought at first, lacking the acute upward curve of insulating fat, and while its tail-flippers looked right, there was something odd about the fore-flippers. Perhaps it was dead; perhaps that was what it was doing all by itself. “Actually, maybe we shouldn’t get too close, we don’t want to frighten it.” “It’s waking up,” Ella breathed. “Is it going to come and see us?” “No, don’t go any closer, it might not be safe, Ella please, no, don’t –” And then the seal turned its head and he saw that they were stalking a woman, small and round and sturdy, lying in the sunlight in a thick black wetsuit that covered her from cap to toe, and now was sitting up and looking at them. “Sorry,” he muttered, trying to take Ella’s hand so they could get away. The woman shaded her eyes with her hand so she could see them better. “We thought you were a seal,” Ella said. “There are seals around here,” the woman said. “But you shouldn’t go near them. They’re hunters, not cuddly toys.”

“I’m called Ella. And he’s called Jacob. And my mum’s called Maggie and my dad’s called Richard and we live –” “Shush, Ella.” Jacob felt as if his face might burn right off his bones with embarrassment. “And I’m Mrs Armitage.” She got to her feet, taking her time about it. Her face was brown, her gaze piercing. “Do you know there’s no way off this beach?” Jacob looked at her blankly. “We got down here.” Mrs Armitage nodded towards the steep slope of earth. “That’s not a path, that’s a cliff-fall. Coming down is one thing. But if you try and climb back up it, it’s liable to come down on you.” “Oh. Okay. We’ll find another path then.” “You won’t find any. There are no safe paths down here. And you can’t climb the cliffs, they’ll come down on you.” “Jacob,” said Ella, her eyes widening. “Shush,” said Jacob. “It’ll be fine.” “But how are we going to get home?” “We’ll be all right, Ella! Stop fussing!” “You’d better come with me,” said Mrs Armitage. “In my boat, I mean. I’ll row you round to the next cove. You can pick up the path and walk back.” “We’ll be fine,” said Jacob. “You’ll drown if you don’t,” said Mrs Armitage, her voice as flat and calm as a millpond. There was no way off the beach. Or was there? What if this strange woman was simply telling them this so she could lure them out onto the water? “Have we got to go near the sea? Jacob, have we got to go on the boat?” Mrs Armitage was older and smaller, he could probably fight her off if he had to, but what if he couldn’t? And what if she was right about the beach? What was the right thing to do? “Ella, will you just shut up, please!” “I don’t want to go on the boat, I don’t want to go on the boat, please don’t make me go on the boat, the sea will get me!” Ella clung to his leg like a bramble. Her face was white. Jacob realised for the first time the scale of her terror. And he’d made her come down here… “Ella?” Mrs Armitage knelt down at Jacob’s feet. “Ella? Listen to me. I need to tell you something.” “She doesn’t like strangers,” said Jacob wretchedly. “Don’t, you’ll frighten her.” Mrs Armitage took no notice. Instead she smoothed Ella’s hair back to expose the tender pink shell of her ear. She put her mouth against it and whispered. And to Jacob’s apprehensive surprise, Ella’s grip on his leg began to loosen and she turned her face towards Mrs Armitage. “Shall we get on my boat now?” Ella’s face was white, but she nodded and held out her arms. “No, I’m not going to carry you, you can walk.” As if Mrs Armitage had cast a spell on both of them, they trailed in her wake towards the waiting water. “Take your trainers off and roll your jeans up. No, don’t carry them, tie the laces together and hang them round your neck. And the little one needs carrying.” She scooped Ella up under one arm, not the way a woman would normally lift a child but like a farmer lifting a lamb, and held her out to Jacob. The water was so cold it felt as if it hated them. Jacob gritted his teeth and kept wading. Ella’s foot slipped briefly below the surface, and she whimpered and drew herself up against his chest. “The boat’s going to be heavy,” said Mrs Armitage. “So I need you to get in when I say and sit where I say and sit still, you understand me? And don’t put your feet on my scuba gear.” Stacked beneath the seat was a pile of equipment – a tank, a mask, some sort of thing like a thick sleeveless jacket. Mrs Armitage pointed at Jacob. “Pass your sister to me, then get in. Slowly, don’t tip the boat. Now sit right in the middle of that thwart.” “I don’t know what the –”

“The thing like a seat that’s clearly the only place you can sit and that I’m pointing at,” said Mrs Armitage, with no particular emphasis. “And then keep still.” Jacob climbed obediently in. He’d thought the point of boats was to keep the water out, but there was a good inch of sea water sloshing around. He tried not to cringe as it washed over his naked feet. “Now I’m going to pass Ella to you. Sit her on your knee so the boat stays balanced.” Ella’s teeth were chattering with fear and her fingers clung like twigs to the thick black material of Mrs Armitage’s wetsuit. “No, none of that, thank you. Let go. That’s right.” She dropped Ella onto Jacob’s lap. “There you are.” Then there was a quick slither too fast to follow, and Mrs Armitage was effortlessly balanced in the centre of the boat, which – just as she’d said – now rode alarmingly low in the water, with what seemed like only a few inches of woodwork separating them from the waves. Mrs Armitage took the oars and began to pull. This was it. They were officially out at sea with a total stranger. He held Ella as tightly as he dared. Getting the boat moving through the water took a lot of effort. He could see the strain in Mrs Armitage’s face as she wrenched at the oars. After the first few strokes, she paused to push the black cap from her head, revealing cropped brown hair turned tufty and wild by its confinement. “Can I help?” Jacob asked after a while. “I don’t know. Can you row?” “I’ve never tried.” “Then no, you probably can’t help.” She kept rowing. The beach was growing more distant. The silence settled around them like mist. “Our house is going to fall into the sea,” said Ella suddenly. “Ah.” Mrs Armitage nodded. “So you’re the ones. And that’s your house.” He glanced over his shoulder. They were far enough out now that their house was visible. Did this mean his parents, looking out of a window, might be able to see their children afloat on the North Sea with a stranger? He wondered if they were looking for them yet, and how much trouble he’d be in when they finally got home. “It’s not going to fall into the sea,” Jacob told Ella. “Yes it is.” Mrs Armitage’s voice was so flat and calm that it took him a minute to realise he’d been contradicted. “This whole coast is going to disappear in the end.” “Could you stop frightening my sister, please, she’s only six.” “But the good news is,” Mrs Armitage continued as if he hadn’t spoken, “you’re a good twenty feet further from the edge than I am, so mine will go first. So as long as you can still see my house, you’ll know you don’t need to worry. I leave a light on in my bedroom window all night. You’ll be able to see it from your turret window.” She paused for a moment to catch her breath. The boat hopped up one side of a wave and down the other. Ella grabbed onto Jacob’s t-shirt. “I live in the white cottage just along the cliff. My husband chose it. He always liked to be near the sea.” They both looked where Mrs Armitage was pointing. “Then, of course, he ended up drowning in it.” On Jacob’s lap, Ella shuddered. He wondered what would happen if he stood up and pushed Mrs Armitage into the water. “But when your house falls into the sea, you’ll be in the sea too,” said Ella. “And then you’ll drown.” “No, I won’t.” “Yes you will.” “No, I won’t. I told you. I can breathe underwater.” “How? How can you breathe underwater?” “That’s my secret,” said Mrs Armitage. “But I can learn to do it too?” “She’s a scuba diver,” said Jacob crossly. “See those tanks? They’re full of air. She puts them on her back and she can breathe the air through the pipes.”

“A lot of people don’t rate the North Sea as a dive-site. I like it here because you’re not surrounded by holidaymakers making a nuisance of themselves. The water looks muddy but it’s clearer further down. Worse after a storm, of course.” “What is there to see?” “Some good wrecks. Most from the Second World War. A few fishing boats.” When her gaze fell on Ella’s terrified face, her expression softened. “Wrecks are good for the ocean. Fish like them. They make good habitats.” Jacob looked dubiously round at the little boat and wondered how Mrs Armitage could possibly row out far enough to find a shipwreck. “I have another boat,” she said, as if she could read his thoughts. “Bigger than this one. I just use this for pottering around the coast where the water’s shallow.” “Where’s your other boat?” Ella looked around as if it might be hidden under the thwarts. “At the marina, just along the coast from the beach where I’m taking you. You can ask your parents to take you there if you want.” “No, thank you,” Ella whispered. “Ella’s scared of the water,” said Jacob. “No she isn’t. She’s scared of drowning. That’s only common sense. That’s why you have to learn not to drown.” She rested the oars on the rowlocks to catch her breath again. The boat slowed to a rocking, unstable halt. When he looked behind him, Jacob saw the shoreline of another cove, close enough to make out the dogs and people roaming around on it, but too far to swim. Was Mrs Armitage strong enough to get them back to the shore? Was she willing to? Was she even sane? “How about I row for a bit and you –” “No!” Mrs Armitage’s bark shocked him into instant stillness, frozen foolishly in the act of rising from his seat. “Sit still. I told you, we’re too low in the water. If you start wandering around you’ll tip it. Sit back down. Slowly.” Jacob sat back down. “That’s better. So. Why did your parents buy a house that gets more worthless with every year that passes?” “I think it’s what they could afford,” said Jacob, shocked into honesty. Mrs Armitage laughed. “It’s not a bad place to live. Quiet in the winter, but some people prefer that. Not so good for teenagers, of course.” She rested the oars once more. “The tide will carry us in now.” “See, Ella?” Jacob smiled encouragingly. Ella rewarded him with a small stretching of her rosebud mouth. “Nearly there.” Another few strokes. Another break. How deep was the water now? Jacob willed himself to sit still and wait. Mrs Armitage peered down into the water, frowned, rowed another few strokes. “Right, that’ll have to do. Sit tight. Don’t try to get out until I say.” In a slither of neoprene, she slipped over the side and stood thigh-deep in water. “There’s a shelf in the bottom just here, so be careful.” She held Ella as Jacob clambered awkwardly over the side. The water came well above his knees, but when he took a step towards the shore it was just as Mrs Armitage said: a sudden shelf that dropped the water level from his thighs to his calves. “There’s a path at the top of the beach,” Mrs Armitage told him. “It takes you along the cliff to the end of your garden.” She turned her gaze towards Ella. “It goes right past my house, so you could use it to visit me, if you liked. Or you can walk back through the village if you prefer. That takes longer.” “Thanks.” “I’m sorry your house is going to fall into the sea,” said Ella. “Why?” “Because then you won’t have your house any more.” “Then I’ll live in the sea where I belong,” said Mrs Armitage. “Thanks,” Jacob said again, unsure of what else to say.

With Ella in his arms, he began the slow wade back to shore. When Ella’s feet touched the sand, he felt her let out a long breath of relief. “She can turn into a seal,” Ella said to Jacob. “No, she can’t.” “I wish I could turn into a seal.” And then, all in a rush, “Last night I was asleep and I thought the house was falling into the sea and we were falling through the water, and there was an old broken boat and some fish were going to eat our eyes and a crab was going to walk over our skulls.” “Is that why you were so scared? Oh, Ella.” “Is that going to happen one day?” “No, of course it isn’t, that was just a nightmare. Why didn’t you go and get Mum?” “It’s dark on the way to their room.” He sighed. “I tell you what. If you have that dream again, then come and get me. Don’t wake me up or anything,” he added hastily. “But if you’re really scared, you can get in bed with me for a bit. As long as you lie still and don’t wriggle. And you won’t need to be afraid, ever, because we’ll be together.” “Even if the sea comes?” “Even if the sea comes. I promise. Do you want to wave goodbye?” They turned to face the sea and saw that Mrs Armitage was still standing in the water, one hand on her boat, watching them.

Purchase link…..

Giveaway…..

For your chance to win a paperback copy of Underwater Breathing, courtesy of Legend Press, all you have to do is comment ‘Yes please’ on this post and I’ll choose a winner at random! (UK ONLY PLEASE!)

Thanks in advance for joining in!

Good luck!

The Author:

Cassandra Parkin grew up in Hull, and now lives in East Yorkshire. Her short story collection, New World Fairy Tales (Salt Publishing, 2011) won the Scott Prize for Short Stories. Cassandra’s writing has been published in numerous magazines and anthologies. Follow Cassandra on Twitter @ cassandrajaneuk

Reviews…..

‘A dark, powerful and emotional novel with hauntingly beautiful prose. It will compel you to read on even as it sends chills up your spine’ Nicola Moriarty

‘This is a glorious, emotional novel about who we really are, where we belong in the world, and how truly at mercy we are to the events that shape us. I can’t recommend it enough’ Louise Beech

Other books by the author:

The Summer We All Ran Away (2013)

The Beach House (2015)

Lily’s House (2016)

The Winter’s Child (2017)

Check out the rest of the blog tour for reviews, and more, with these awesome book bloggers…..

Yes please

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes please 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes please

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes please 💖

LikeLiked by 1 person